9/11 responder's medical bills mount

Posted by the Asbury Park Press on 06/30/07

Posted by the Asbury Park Press on 06/30/07BY MATT PAIS STAFF WRITER

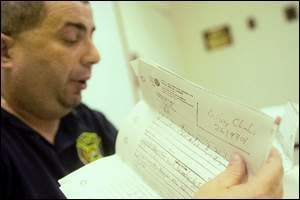

BARNEGAT — Charles Giles arrived at the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001, just as the second jet made impact.

Soon the citywide EMS supervisor was at the base of the towers, helping the people who were evacuated. Able to outrun the collapse of the first tower, Giles' luck ran out when the second came crashing down. Only a timely rescue by a Port Authority police officer saved him.

Giles spent less than 24 hours at Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx before heading back to lower Manhattan. He stayed at ground zero for nearly two months, never giving a second thought to any long-term implications.

Six years after the Sept. 11 attacks, Giles' health has steadily declined, a pattern doctors say is linked to the "black junk" that he inhaled at the site of the fallen towers. Like many responders, he now finds himself saddled with medical bills and a government unwilling or unable to help.

As treatments and costs continue to mount for Giles, the realization that the federal government provides little becomes clear.

"I'm a Republican, and I love George Bush, but they've got to do something," he said.

Giles said he watched Christie Whitman, former New Jersey governor and administrator of the federal Environmental Protection Agency, testify before Congress this week. He was stunned when she continued to assert the government's response was correct.

"If you mix concrete, plastic, jet fuel, human remains, paper, burned steel, cleaning agents and everything else that was there, add 3,000 degrees, it's a recipe for disaster. And we all inhaled that disaster," Giles said.

His illness began with chronic bronchial asthma, then morphed into avascular necrosis. A hip replacement followed, as did osteoporosis. Doctors say his other hip and one lung are likely to fail soon.

"For a 39-year-old, it's kind of rough," Giles said. "I'm a young guy. I have to stay alive for my family."

A husband and father of two who only three years ago took joy in spending 80 hours a week working and volunteering now finds himself out of work and nearly out of money. The 16-year EMS veteran was forced to leave his job with Quality Medical Transport. He has medical insurance but co-pays for a dozen medications total more than $200 each month.

"I get $241.57 a week from disability, and that's it. How do I survive on that?" he said.

By all accounts, Giles should be financially secure. There's the New York Crime Victim Board fund, New York state worker's compensation, even Red Cross money available, and Giles applied for them all. To date, he has yet to receive any governmental assistance.

The only help he did receive came courtesy of the Pinewood Estates Fire Company. His fellow members raised $3,800 during a recent coin drop and, though helpful, his bills continue to pile up.

"I don't want one penny more than I'm entitled to," he said. "There's money out there. They need to stop sitting on it and give it to the guys who are giving their lives."

Giles' problem is not unique, said John Feal, president of the Feal Good Foundation, a Nesconset, N.Y.-based organization that raises awareness about Sept. 11 health effects.

"The government is sitting idle, and the lack of compassion is killing responders," Feal said.

Too often the government provided money for monitoring health of ground zero veterans and rarely provided assistance for treatment or preventive care, Feal said. For the estimated 30,000 responders suffering from Sept. 11-related physical and mental illnesses, that often means bearing a tremendous financial burden alone.

"We need help now," said Feal, a responder himself. "These are people who risked their lives and are heroes, and we've been kicked to the curb like garbage."

One of the groups working to reverse that is the New York Committee for Occupational Safety and Health, or NYCOSH, a nongovernmental group among the first to identify hazardous conditions at ground zero.

The group helped extend the statute of limitations on filing claims and played a role in pushing legislation making volunteers eligible for worker's compensation. Funds are available, but thousands eligible for assistance are unable to navigate through a bureaucratic maze, said Jonathan Bennett, NYCOSH's public affairs director.

"The response on the part of the government and charities has been uncoordinated. It's a big public health problem," he said.

The reluctance of government to become the lead agency in providing and coordinating relief has caused widespread misdiagnosis and ineffective treatment for many suffering responders, Bennett said.

"There needs to be a recognition that this is a specialized kind of medicine that you just can't turn over to your family doctor," he said. "There's a government responsibility to deal with this."

http://www.app.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20070630/NEWS/706300404